- Home

- David Maidment

A Privileged Journey

A Privileged Journey Read online

Painting by railway artist David Charlesworth, commissioned by the author, of 30777 Sir Lamiel on the 5.9pm Waterloo–Basingstoke passing Surbiton, February 1960.

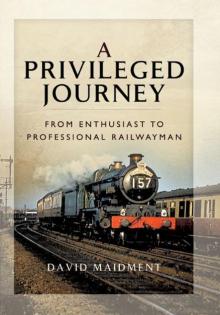

Cover: 4087 Cardigan Castle at Reading West on the down ‘Mayflower’, the 5.30pm Paddington–Plymouth, April 1958. (R. C. Riley)

All photographs in the book are by the author, except where otherwise credited.

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Pen & Sword Transport

An imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street, Barnsley South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright © David Maidment 2015

The right of David Maidment to be identified as the author of this work had been

asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording

or any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission

of the publisher, nor by way of trade or otherwise shall it be lent, re-sold, hired out

or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding

or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition

including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN: 9781783831081

EPUB ISBN: 9781473859494

PRC ISBN: 9781473859487

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology,

Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime,

Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, and

Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When,

Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Typeset by Milepost

Printed and bound by Imago Publishing Limited

All royalties for this book will be donated to the Railway Children charity

(reg no. 1058991)

(www.railwaychildren.org.uk)

Acknowledgements

To those who stimulated and shared my interest in railways and especially the steam engine - my father, Jack Maidment, Great Uncle George, Aunt Enid, Cedric Utley, John Crowe, Alastair Wood…

Contents

Ready for departure — 30777 Sir Lamiel at Waterloo on the 5.9pm to Basingstoke, May 1960.

Preface

Chapter 1:

In the beginning

Tableau 1:

Surbiton station March 1950, 4.10pm

Chapter 2:

What we were allowed to do in 1950

Chapter 3:

My first camera

Tableau 2:

Euston–Willesden, 1953

Chapter 4:

Devon holidays

Tableau 3:

Goodrington Sands, August 1952

Chapter 5:

The Charterhouse Railway Society

Tableau 4:

Oxford station, November 1956

Chapter 6:

Living in Woking, 1957-62

Tableau 5:

Hungerford Bridge, March 1958

Chapter 7:

The wider horizon

Chapter 8:

Old Oak vacation

Tableau 6:

Old Oak Common Shed, July 1957

Chapter 9:

Munich University, 1959

Chapter 10:

My first privilege tickets

Chapter 11:

Weekly season ticket to Reading, 1959/60

Chapter 12:

Working for British Railways - the first year

Tableau 7:

Platform 8, Paddington, July 1961

Chapter 13:

No 4037 - the Western Region’s highest-mileage locomotive

Chapter 14:

Commuting in the London Division

Tableau 8:

On the 5.30pm Oxford, April and May 1962

Chapter 15:

Old Oak Common management training

Postscript:

Appendix:

Train-log tables

Preface

David Charlesworth’s representation of 4087 Cardigan Castle on Llanvihangel Bank with a Plymouth–Manchester express c1963 — a painting commissioned by the author and used on a Christmas card for the Railway Children charity.

This book has been written for fellow railway enthusiasts — particularly those seduced by the magic of the steam locomotive. For some, hopefully these chapters will elicit similar memories and permit them to revel in unashamed nostalgia. For others — perhaps those who were not fortunate enough to experience Britain’s steam railways in their heyday — it may give a feel of what it was like to live and work on the railway when Britain had more than 18,000 working steam locomotives. From the age of two I was entranced by railways and their trains. By the time I was eight I was a trainspotter, and by the age of eleven I was being allowed to travel unaccompanied to London to pursue my hobby. Later I decided to turn my hobby into a career.

In 1960 it was still acceptable to admit to being an enthusiast and become a railway manager. For many senior managers at that time it meant that they knew you were motivated, were aware of the basics of the job and had a more than average awareness of the geography of Britain’s vast railway system. Later, as the new traction began to appear, interest in steam locomotives became a handicap that one had to hide if one was ambitious. Steam locomotives were old-fashioned, and showing an obvious interest in them meant you were backward-looking, not the thrusting, positive ‘young turk’ that the new generation of managers was seeking. I was nearly removed from the Western Region’s management-training scheme in 1962 when my report on the three months’ training at Old Oak Common had too much to say about the efficiencies or otherwise of the run down of steam, rather than dwelling on the opportunities for quicker ‘dieselisation’. Perhaps they should not have sent me to train at a depot that in May 1962 still had 170 steam locomotives and only 20 diesel shunters. The Assistant General Manager, Lance Ibbotson, castigated me for not visiting the new Landore diesel depot within days of taking up my new training schedule in South Wales. The fact that at the time it was just a muddy building site held no excuse. So I became more circumspect about my enthusiasms and survived.

This book relies for some of the chapters on articles I’ve written over the years for the monthly magazine Steam World and a couple from Steam Days. Other chapters are entirely new, and all have been added to, amplified or updated. The photographs are from my vast collection taken with relatively cheap black-and-white-print cameras — a folding Kodak Brownie with fixed f8 aperture and 1/25sec standard shutter speed, followed in my teenage years by an Ensign Selfix that was still restricted by its slow shutter speed but had a superb lens. In the following pages I recall my experiences and railway training to the end of 1962; the intention is that a second volume will cover the final days of British steam until 1968, followed by a frantic rush round the railways of Europe before steam disappeared there too, and will also explain how my later railway career allowed me to continue to experience steam at home and abroad.

I owe thanks to a large number of people, but I’ll select a few for special mention: firstly my parents, for encouraging and then tolerating my hobby, a

nd my wife, Pat, for permitting it to be such an important part of my life; also my childhood friend Cedric Utley, who accompanied me on my earliest train-spotting trips, Martin Probyn, Conrad Natzio, Philip Balkwill, Jim Evans and other members of the intrepid Charterhouse Railway Society, Alistair Wood, who taught me the rudiments of train timing (although he was always sceptical of my accuracy and Western Region bias), Colin Boocock, who encouraged and helped me to write about my experiences, and those BR colleagues who encouraged me in those early days (or at least tolerated my interests) — Rodney Meadows, who, as Assistant Train Operating Officer (Bristol), supervised a ‘short work course’ which opened my eyes to a possible railway career, WR Assistant General Manager George Bowles, who recruited me, and Ray Sims, Shedmaster at Old Oak Common, who indulged my enthusiasm; then, much later, Frank Paterson, who encouraged me to reflect on my ‘railway life’ by getting me to give several long interviews on tape for the National Railway Museum’s oral-history archives, recalling many of the experiences that gave rise to this book.

All royalties from this publication will be donated to the Railway Children charity, which I founded in 1995 with the help of colleagues in the railway industry. A description of how this came about and of the work it undertakes can be found in my self-published history of the charity — The Other Railway Children — and on the charity’s website (www.railwaychildren.org.uk).

Chapter 1

In the beginning

I am four years old. I am sitting in a nursery school howling my head off. In front of me on the plastic table I have made a barricade of toy bricks and in it placed my book, opened at my favourite page, a picture of the big green steam engine called Lord Nelson. The teachers sent my mother away saying, ‘leave him, he will soon get over it once you have gone away’. They are wrong. I have howled all morning, through lunch, and now it is early afternoon. The other children are doing their best to ignore me; the teachers are getting frustrated because of the din. They cannot phone home. We have no phone. They persuade me in the early afternoon to look at another book. For a few minutes I stare at a photo of the royal princesses — I remember a long hard look at the seven-year-old Princess Margaret Rose, ignoring her older sister — and then I return to my train book. They wait until my mother comes, and then they say ‘it’s no good, don’t bring him tomorrow; bring him only when he’s old enough to start primary school.’ I am still sobbing, although I’ve run out of tears. The bricks are cleared away. My books are closed and put safely in my mother’s cycle saddlebag.

A year later I go to school. It is the same place, but different. I am a year older. There is something active to do. I want to learn to read and write. My father is still away in the army. I do not know what he does or where he is, but sometimes he comes home on leave, and we see him off again at the station. He always takes me to see the engine. He told me once that he remembered Queen Guinevere. We get into the train before departure time to say farewell, and I panic because I think the train will take us with him, and we have to get out lest my mother should be embarrassed by my piercing screams. I don’t understand train timetables yet. I receive small letters from my father. He always draws the picture of an engine in the top right-hand corner of the notepaper — stylised like my toy train I pull around on the carpet.

My earliest memory of all is of standing at the bottom of steps to the platform of Shrewsbury station (we had been evacuated to Shropshire for a while) waiting for my father to book his soldier’s warrant ticket and being lifted to the top just in time to see the tail light of the London express disappearing along the platform. I can remember the frustration of not being allowed to look out of the window on the next train (two hours later) because it was dark and the blackout. I was three years old. I’m told that even earlier I insisted on my mother taking me for a walk in my pushchair the two miles from our home in East Molesey to Esher Common to see ‘proper’ trains (the electrics at Hampton Court apparently didn’t count) — you couldn’t do that easily now as the growth of trees and shrubs would obscure the view.

The author’s favourite ‘Castle’, 4087 Cardigan Castle, surprises him at Paddington, arriving with the 9.30am Minehead, 9 August 1952.

My first proper ‘engine’ memory is travelling home from Bristol near the end of the war. I can visualise a double-headed train at Bristol with ‘Castle’ No 4087 and a ‘Hall’. The date: 26 December 1944 (Boxing Day). I know because I still have the ticket — soldier’s-leave child return, Shirehampton to Hampton Court. The place is Bristol Temple Meads, I am six years old. We are going home, and there are crowds on the platform. But my father takes me to see the engine; he always did, and I associate my father’s army departures and arrivals with being taken to see the engine. And there they are, two engines, 4087 Cardigan Castle and an unremembered ‘Hall’. And when we get to Paddington, there on the buffer-stops is just the one, Cardigan Castle. I can see it now and feel the small boy’s puzzlement. How can it be? What happened to the other engine?

When, a couple of years later, my father bought me my first Ian Allan ‘ABC’ I underlined 4087 in that pristine book before I left the house on my first train-spotting trip. And there it’s always stayed. In later years it was always special, I was at the end of Platform 8 at Paddington with dozens of other small boys in the summer of 1952 and fired my simple Kodak camera at a number of incoming expresses with mixed success, and suddenly one was revealed as 4087. It was the only shot I took that day that really satisfied me.

Years later I was stationed on BR’s Western Region for my management training. During my time at Old Oak Common in the spring of 1962 (described in Chapter 15) I was on the footplate of 4704 on the night goods to Oxley when I spied 4087 on a night fast freight for the West of England, gleaming in the reflected lights of Paddington goods yard, and was tempted to change footplates … And a few days later, after a superb ride from Swansea to Paddington on No 5056, I was returning to my Twyford digs on the rather mundane 7906 when, around Taplow, the 12.5pm Milford Haven–Paddington swept past with Laira’s 4087, nearly ten minutes early — why, oh why, had I not waited at Swansea for the next up express? (And what was a Laira ‘Castle’ doing on a Landore ‘Castle’ turn?) Six months later I was practising Work Study techniques in Laira diesel depot in the snow, and there she was again — stored but lovingly cared for, ready to be restored to traffic the following month. Finally, in the spring of 1963, waiting at Pontypool Road for the 2pm Plymouth North & West express, I saw the familiar white painted smokebox-door hinges, the missing front numberplate, the Davies & Metcalfe lubricator high up beside the smokebox and I knew, 4087 again. Climbing Llanvihangel Bank in the setting sun, I’m hanging out the window, listening to the crisp exhaust as we make light of the gradient, the new foliage glistens, the Sugar Loaf broods over us. A magic memory!

Our first postwar holiday was at Brighton and we travelled there by the ‘Brighton Belle’. I must have been a typical bored boy on the journey and I can still hear my father saying — in some exasperation — ‘Well, why don’t you collect train numbers like other boys?’ So I did. I still wonder how much he later regretted that chance remark. A favourite maiden aunt who lived in Brighton soon cottoned on to my interest, and every time we met she enhanced her reputation by producing a new 1/6d Ian Allan booklet in the series ‘My Best Railway Photographs’; my first was of the Great Western by Maurice Earley, the second a book of Southern photos by O. J. Morris.

Guildford’s shed pilot (and the author’s first footplate experience), Hawthorn Leslie 0-4-0ST 30458 Ironside, at Eastleigh 1954 after withdrawal. (Manchester Locomotive Society collection)

Uncle George’s one-time engine, ‘D15’ 466, at Eastleigh in the 1930s.

(J. M. Bentley collection)

I have to admit that my loyalty was for the Great Western (the imprint of No 4087 and all those photos in Maurice Earley’s book did their job only too well), but although my career developed on the Western Region, I lived until 1962 on the Southern, so its t

rains were the familiar ones.

I can’t really explain my passion for trains, which began at such an early age. Perhaps I associated trains with meeting my father when he was so often absent during the war years. My only other railway connection was my Great Uncle George, husband of my paternal grandmother’s sister. She, Aunt Kate, had been one of Queen Mary’s maids in the Brunswick Tower at Windsor Castle with my grandmother, and after her marriage to George Newman, an engine driver, had moved to Guildford. Uncle George had worked Guildford top-link turns on the Waterloo–Portsmouth direct line during the 1920s with his ‘own’ engine, Drummond ‘D15’ 4-4-0 466, but had retired through ill health in 1929. (He eventually died aged 98 in the 1970s!) In the late 1940s, when I was nine or ten, I’d visited them for the day, and my uncle, as a treat, took me down to Guildford engine shed and put me on the footplate of the shed pilot, 0-4-0 saddle tank 30458 Ironside. My main memory is of being in the diminutive cab as we hauled a dead locomotive onto the turntable and burning my shins on the open fire, as I was wearing only short trousers.

In the autumn of 1949 I started at Surbiton County Grammar School and travelled daily from Hampton Court. The school stood beside the South West main line, just on the Waterloo side of Surbiton station, high above the embankment there. A few of us collected each morning in a small clearing above the line (you can’t do it now — the undergrowth is too thick, and the school is gone) to see the action before the school whistle blew at 9 o’clock. We watched the 8.30am Waterloo–Bournemouth with its Nine Elms ‘Merchant Navy’ or ‘West Country’ sidle beneath the high road bridge, braking for the Surbiton stop. And simultaneously and almost noiselessly apart from the distant whistle as it approached the main up platform at speed would come a malachite-green ‘Lord Nelson’. We soon lost interest in this because within weeks we’d copped the whole class!

A Privileged Journey

A Privileged Journey