- Home

- David Maidment

A Privileged Journey Page 2

A Privileged Journey Read online

Page 2

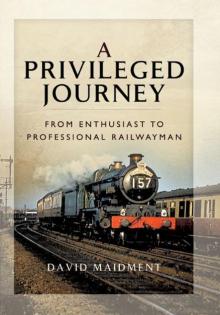

‘King Arthur’ 30455 Sir Launcelot on a semi-fast train from Basingstoke passes just below the point at which Surbiton County Grammar schoolboys trainspotted before the morning bell sounded, 6 February 1957.

30749 Iseult passes Surbiton with a semi-fast to Basingstoke — a replica of the scene the author had witnessed in 1950. (Robin Russell)

The evening, whilst waiting for the 4.25 home on Surbiton station, was even more interesting. School finished at 4pm sharp and although I couldn’t get the 4.5, I was at the station at least by 4.10 in time to see the up ‘Atlantic Coast Express’ roar through with its Exmouth Junction ‘Merchant Navy’ (usually 35022, 35023 or the newly painted blue 35024) and almost simultaneously see the 3.54pm Waterloo–Basingstoke come bucketing down the track working hard with one of its collection of Nine Elms veterans — Class T14 ‘Paddleboxes’ 444, 445, 447, 460, 462 and the already renumbered 30446 and 30461, which would leave a fog of pungent brown smoke hanging under the wide platform overbridge. These would be increasingly interspersed with one of the Urie ‘H15s’ or Class N15X ‘Remembrances’ or one of the Urie or ‘Scotch’ ‘King Arthurs’ — I can still recall in my mind’s eye 30741 Joyous Gard, 30753 Melisande, 30776 Sir Galagars and 30791 Sir Uwaine. Most of the ‘Arthurs’ were in malachite-green livery with ‘BRITISH RAILWAYS’ painted on the tender in the old Southern style.

Two of the Drummond T14 4-6-0s, that regularly hauled the 3.54pm Waterloo – Basingstoke in 1949-50, 444 and an unknown sister at Nine Elms in 1950, alongside 34023 Blackmore Vale.

(Lewis Coles/MLS Collection)

‘Merchant Navy’ 35024 East Asiatic Company (in blue) passes Surbiton on the 3 o’clock Waterloo–West of England c1952. (Robin Russell)

30806 Sir Galleron between Brookwood and Woking with the Eastleigh van train — still the same as seen daily in 1950, but recorded in 1960.

After a couple of down-line electrics, taking some of my friends to Oxshott and Esher respectively, the ‘ACE’ would be followed by the Eastleigh van train — mixed ECS and parcels, with the possibility of almost anything at the front end. Although booked for an Eastleigh-based ‘Arthur’ or ‘H15’ it was obviously used for running-in ex-works locos. I remember seeing at least one ‘L12’ (30424), and just once the unfamiliar outline of a large-diameter-chimney ‘Schools’, 30917 Ardingly, surprised us all and caused extraordinary scenes of merriment among the crowd of small-boy witnesses — after all, few of us at that stage could afford a trip to Charing Cross from our meagre pocket money.

Finally, just before my own electric slunk around the corner from under the high bridge below the school, the Clapham Junction milk empties, a train on which No 34031 Torrington performed for months, would charge through the station amid the clatter of its six-wheelers, followed by the pungent smell of Kentish coal. And all the time a ‘K10’ or ‘L11’ 4-4-0 would be slithering up and down the adjacent coal yard (now a car park) — more often than not 30406, or one of its sisters 405 and 413. On one memorable occasion it was, of all things, the malachite-green royal ‘T9’, 30119. If for any reason I got out of school early I would see an up Basingstoke local with an ‘N15X’ (Nos 32328 Hackworth in lined BR black and 32330 Cudworth in malachite green stick in my memory) and a pick-up freight with one of Feltham’s magnificent ‘H16’ Pacific tanks (30516-20). For some obscure reason I used to circle the numbers of the engines I’d ‘copped’ in green biro in my Southern ‘ABC’ instead of underlining as most other boys did.

Looking back now, I realise that in those two years I never failed to see those four steam services between 4.5 and 4.25pm, and the sheer consistency of the Southern Region’s punctuality could be taken for granted. One of my schoolmasters at Charterhouse, which I attended after 1951, lived near Worplesdon, his garden backing onto the Woking–Guildford main line, and he told me that his party trick was to take visitors to see the hourly fast Pompey electrics crossing each other at the bottom of his garden — and it never failed!

It would have been around this time that I discovered the monthly Ian Allan magazine Trains Illustrated. My first purchase was No 10, although since then I’ve managed to pick up a couple of the earliest editions. I used to long for the time each month when the new magazine would arrive and would pore over it until the next one appeared. I can remember those early editions and the photos much better than those in more recent magazines. It was the regular article by Cecil J. Allen on locomotive practice and performance that inspired me in particular and led later to my own interest in recording locomotive performance, although I compiled no serious logs until about 1956.

Then, a couple of years later, around April 1951 (we’d still maintained our interest), I was at the top of the cutting, waiting for the school bell to go, but on this particular morning, for some unknown reason, I was alone. There was something odd about the approaching westbound train — the whistle in the distance was a blood-curdling chime, and the approaching locomotive was not an air-smoothed Bulleid, nor was it an ‘Arthur’ or ‘Nelson’. And suddenly it emerged from beneath the high bridge, 70009 Alfred the Great, a brilliant green apparition, and the scales tumbled from my eyes — because just a few weeks earlier I’d seen the dramatic photo of 70000 on the cover of the March 1951 Trains Illustrated. I couldn’t wait to tell my friends. And they didn’t believe me! It was such a let down. So I waited the next day — the others were losing interest and couldn’t be bothered — and it was 70009 again. The next day I waited with trepidation, as my sceptical friends had turned out to call my bluff, and it was a ‘West Country’. The others gave up until the following Monday, and then, to the surprise of all of us, it was not a Bulleid, nor 70009, but the other ‘Britannia’ that was loaned to the Southern while a couple of Bulleid Pacifics were tried out on the Great Eastern, 70014 Iron Duke. The relief when 70014 did not let me down before my friends!

Photograph of brand-new BR Standard Pacific 70000 Britannia on the cover of Trains Illustrated March 1951.

Tableau 1

Surbiton station, March 1950

It’s a damp late afternoon in early March, and Cedric, Robert and I are scampering over the Ewell Road Bridge, our satchels bouncing on our backs, full of the homework set by our form master, Mr Bolt. The clouds have hung around all day, and although it’s only just after 4 o’clock it already seems like dusk. We’re hurrying because we want to be at the station before the ‘Atlantic Coast Express’ charges through. Then, as we leave the main road and turn off past the leafless bushes that screen us from the sight of the four tracks down below, Cedric and Robert begin to scuffle with two of the other boys in our class who are going in the opposite direction to us, to Berrylands and New Malden. I’m impatient. If we don’t hurry the express will tear past, and we shall just see the smoke billowing through the trees and hear the howl of the mournful hooter. I make to go on ahead, ears straining for the distant sound. ‘It’s coming,’ I yell. ‘Come on, we’ll miss it!’

My friends break off from their tomfoolery, and we clear the thicket and come onto the open pathway above the concrete embankment walls just in time, for there’s a prolonged wail from the approaching express which bursts from under the station overbridge and tears past us in a blur of green, smoke swirling around the coaches labelled Padstow and Bude and Ilfracombe, the staccato thunder of the wheels drowning the soft exhaust of the ‘Merchant Navy’ already disappearing under the high bridge by our school.

‘Holland-Afrika Line again,’ moans Cedric. ‘No need to have hurried — it’s always the same.’ It isn’t, but I don’t argue. You never know, it might be different one day. We hurry down onto the platform, for there’ll be a train on the down line in a minute. We’re at the bottom of the steps, and I can already see the billowing white smoke in the gloom, under the bridge. This train is working hard — I can hear the pounding of the engine, the deep roar from the chimney, the rhythmic ‘pshht pshht’ of steam from the cylinders — and as the malachite-green engine rocks past me, its exhaust richocheting off the

overbridge and engulfing us boys on the platform, I read ‘30744’ — Maid of Astolat. It’s gone in an instant, its short train clattering past and hurrying westwards, the tail lamp just visible in the dusk, shining through the smokescreen now trailing in its wake.

Scarcely has the sound of its exhaust dwindled in the distance than Robert’s electric train comes tentatively under the bridge, the station loudspeaker booming its familiar message, ‘Esher, Hersham, Walton, Weybrdge, West Weybridge, West Byfleet, Woking, the front four cars for Brookwood, Ash Vale, Aldershot …’ The voice fades under the hum of the approaching train, brakes squealing as it stops, and Robert jumps in, shouting out some last comment on our Geography homework. At the same time there is a sudden thunderous slip behind us and a clanging of buffers as the coal-yard shunter, ‘L11’ 30406, jerks into action, drawing out a raft of wagons towards the throat of the sidings. Cedric and I both look round, turning our backs on the departing electric and stare at the sparks still descending. The glare from the open firebox door illuminates the driver tugging at the regulator, while the fireman is hanging nonchalantly out of the other side of the draughty cab. The engine slithers to a halt amid a further clanging of buffers, and we are so absorbed in this spectacle that we nearly miss the Eastleigh van train, which has been sidling up on us. We are alerted as we suddenly hear its engine open up as its driver spots the signal at the far end of the up platform change from double-yellow to green, and ‘Scotch Arthur’ 30770 Sir Prianius accelerates slowly past us with a long string of parcel vans. We count them; I make it nineteen, Cedric swears there are twenty, and we try to count again, but the ‘N15’ has got hold of its train now, and the empty vehicles are accelerating past us at an ever-increasing tempo.

It’s nearly time for our train now. Will it come before the milk empties? We’re at the front of our platform, ready to join the first car of our four-coach EMU, right opposite where 30406 is straining to haul another half-dozen wagons from the back of the coal yard. I’m not that bothered. Both the ‘Arthurs’ tonight were ‘cops’, and I’m satisfied. The milk train will only be Torrington again — it has been for over a fortnight now. And indeed I spy the 4.25 to Hampton Court coming under the bridge just as a wisp of steam appears above it, and I watch the ‘West Country’ gain on our slowing electric. And I’m wrong. It’s a different Exmouth Junction ‘West Country’, Yes Tor. Three cops tonight. Cedric and I look at each other in glee. We dance a jig, and in our surprise and excitement we almost forget to join our train, which has now stopped silently behind us. We scamper in and slam the door, pull out the strap and let the window down with a clatter so we can breathe in the pungent smell of the brown haze left behind by the shuffling pacific and its clackety-clack six-wheelers. We set off in pursuit of it, but it’s got too great a head start, and all we catch is the remnant haze of brown smoke drifting in the drizzle that is now swirling into our compartment. We close the window. The show is over for another day.

Pages from the author’s 1949 Ian Allan ‘ABC’ trainspotter’s book of BR Southern Region locomotives.

Chapter 2

What we were allowed to do in 1950

‘M7’ 30130 at Waterloo, 29 May 1950. (Cedric Utley)

Boys of twelve were allowed to put sandwiches, an apricot ‘Harvest’ pie and a bottle of Tizer in a duffle bag, buy a cheap day return to London and spend the day on their own going around the Circle Line, stopping off at Paddington, Euston Square, King’s Cross & St Pancras and Liverpool Street before returning to Embankment and walking across Hungerford Bridge back to Waterloo in the hope of seeing a St Leonards or Bricklayers Arms ‘Schools’ poking its head out of Charing Cross station. Permission was granted even more easily if one went with a friend, although I suspect two heads on these occasions were marginally more enterprising and therefore more dangerous than one.

The first evidence I have of such a visit is a page of four rather amateurish photos taken by my friend Cedric thirteen days after my twelfth birthday. A splendid but not-quite-horizontal photo of Arethusa at St Pancras, complete with Fowler tender still showing ‘L M S’ very plainly, a far-from-horizontal photo of Hawksworth tank 1504 in the distance at Paddington (why that instead of Caledonian-blue ‘Kings’ and Brunswick-green ‘Castles’?), a distant shot from Platform 8 of the locos around the turntable in King’s Cross yard — an ‘N2’, Dante, Raby Castle (I think) and what looks like an ‘L1’ — and a fine photo of ‘M7’ No 30130 at Waterloo, awaiting its next ECS duty. Cedric became my bosom pal. He’d just moved to East Molesey from Yorkshire, and we joined the 8.25 from Hampton Court to Surbiton together to go to our grammar school.

But the Southern’s Western Section engines amid all the electrics seemed too humdrum, and so we made our plans to look for more exotic sights in London, and our mothers acquiesced. It was 29 May 1950, that first trip that I remember. A Saturday, of course; it was compulsory Church and Sunday School on Sundays. The old pre-Grouping three-car unit, augmented to four cars by the addition of a Bulleid trailer, all-stations to Waterloo in exactly the same time as the scarlet Class 455 units do it now, would be in Waterloo before 9am. We would look out for an old second-class compartment, long since downgraded to third, because it gave more legroom for standing around the window trying to catch a glimpse of mysterious goings-on in Stewarts Lane before looking for engines backing out of Nine Elms, awaiting their turn to parade at Waterloo.

It was the Northern Line to old Euston, in time for our first quarry, the ‘Royal Scot’. A quick look to see what had arrived at platforms 1, 2 and 3, usually night sleepers still slumbering at the stop-blocks, or perhaps something already backing its train up Camden Bank towards Willesden carriage sidings, then all haste to platform 13, in time to wait with trepidation for the tender of the ‘Duchess’ to appear in the distance, descending the bank — rumour had it that the train was diagrammed for a Polmadie ‘Duchess’, no less, to our innocent eyes a rare exotic beast. It was blue, of course, 46227 Duchess of Devonshire — not just my first Polmadie locomotive, but my first ‘Duchess’ too. The business end of platform 13 was timbered and very narrow, so the spotters were crammed into a small space, all pushing for a glimpse into the holy cab and the roaring fire, as the engine deafened us by suddenly expulsing a tirade of steam. After its departure (and, I suppose, the 10.40 to Perth, which I cannot remember) the station seemed strangely quiet. The arrival side was now empty, the sleeper trains now safely stowed at Willesden. I just remember an apple-green ‘Royal Scot’, 46169 The Boy Scout in its experimental livery, and an unrebuilt and unnamed ‘Patriot’, 45509, simmering halfway down the platform lit by shafts of sunlight pouring through the smoky roof.

‘Jubilee’ 45696 Arethusa photographed by a friend of the author at St Pancras on a lunchtime train for Derby, 29 May 1950. (Cedric Utley)

Disappointed at the lack of further action, we walked to Euston Square and made for Paddington, emerging on the Hammersmith platform amid ‘sixty-oners’ (‘Large Prairie’ tank engines of the ‘61xx’ class) on non-corridor locals for Slough and Reading, and looked across at the phalanx of ‘Kings’ and ‘Castles’ ranged at the head of platforms 1-5 in glorious symmetry. We would run across the passenger bridge halfway down the platforms lest a train steal a march on us and leave before we had gained its precious number.

At first we used to join a few boys at the far end of platform 1, beside the metal advertisements on the brick walls for ‘Tangye Oil Pumps’, in order to be subsumed into the thunderous exhaust of departing trains as the smoke and steam crashed back from the bridge under Bishop’s Bridge Road. That first day I remember the filthy tender of the erstwhile royal engine 4082 Windsor Castle backing around from the parcels deck (platform 1A), its front end swathed in steam, onto a Worcester train — before, that is, it swapped identities with Bristol Castle for the King’s funeral and became 7013 for evermore, outliving the 25-years-younger 4082 by several months. I remember 5093 Upton Castle racing in past the majority of small boys on platform 8 with t

he ‘Red Dragon’ and (now of greater interest) underlinings in my notebook of a couple of ‘Princesses’ — Nos 4051 and 4052 and an early survivor, 4007 Swallowfield Park — and not realising their rarity or that of the lone ‘Saint’ I saw in London, 2949 Stanford Court, that lunchtime. Seen from platform 1, incoming trains surprised the unguarded spotter by arriving suddenly from behind a motley collection of small hutments and entered the platforms with unusual rapidity.

‘Star’ 4007 Swallowfield Park arriving at Paddington c1950 with a train from Worcester. (Anon)

An array of locomotives waiting to depart Paddington on 14 February 1958. From left to right are 5935 Norton Hall, 70021 Morning Star on the 1.55pm to West Wales, 5029 Nunney Castle on the 1.50 relief and 6020 King Henry IV on the 2.10 to Wolverhampton.

On we went to King’s Cross, using the Hammersmith Line so that we could see action up to the moment the tube train appeared from Subway Junction. A quick nip into St Pancras produced the one ‘namer’ — the aforementioned 45696 Arethusa — but a solitary ‘Black Five’ was the only other offering, apart from a couple of Stanier 2-6-2 tanks, so we sought bigger scalps next door. A couple of ‘A1s’ graced the arrival platforms, one being King’s Courier, but we joined the throng at the end of platform 8 with its vista to the yard, agog to see what would emerge from the Gasworks Tunnel, which seemed always on the brink of producing its magic from the smoke curling from the tunnel portal, several minutes after the last action. While we waited we remembered our soggy sandwiches and took a swig of Tizer, for we had been so absorbed and excited that we had not noticed any hunger pangs. Then a shadow formed in the swirling smoke, a corridor tender emerged, and the cry went up long before we saw the streamlined shape, a ‘Streak’. Walter K. Whigham, 60028. ‘N2s’ chugged out from the ‘drain’ with their archaic sets of quad-arts but went virtually unnoticed — a scrawled number to underline later, but no picture etched on the inner eye. A ‘V2’ clanked in from the north over on the far side, but the eyes of small boys were drawn inexorably to the glamorous pacific. Who was Walter Whigham? Did it matter? The driver played his chime whistle for us, a short peep at first; then, as he left with the Newcastle express, he exhibited its full glory, a spine-tingling chord in crescendo, and repeated the plangent and prolonged orchestration as the ‘A4’ plunged into the tunnel, the coaches disappearing smoothly, one by one into the murk, and silence descended on the awestruck assembly.

A Privileged Journey

A Privileged Journey